Week 11: Recursion

Announcements

-

Lab 9 is available now.

Week 11 Topics

-

Recursion

-

Iteration vs recursion

-

Base case

-

Recursive case

-

Recursion on lists and strings

-

Graphics

-

Merge Sort

Monday

Recursion

Any function that sometimes calls itself is known as a recursive function. In most cases, recursion can be considered an alternative to iteration (loops). Instead of defining a loop structure, recursion defines a problem as a smaller problem until it reaches an end point. There are three requirements for a successful recursive function:

-

Base case: each function must have one or more base cases where the function does not make a recursive call to itself. Instead, the problem has reached its smallest point, and we can begin returning back the small solutions.

-

Recursive case: the function makes one (or more) calls to itself. The call must use a different argument to the function (or else we keep making the same recursive call over and over again!). Typically, the problem gets 1 smaller.

-

All possible recursive calls must be guaranteed to hit a base case. If you miss one, your program is susceptible to an infinite recursion bug!

Example: Print a Message

The printmessage.py program prints a given message n times. We’ve already

seen how to solve this problem with a loop, but let’s explore how we can solve

it without a loop using recursion. To understand what’s happening with

recursion, it’s often helpful to draw a stack diagram. The key concept is that

Python treats the recursive function call the same as any other function

call — it places a new stack frame on top and begins executing the new function.

The only difference is the function in this case has the same name.

Example: Summing Integers

We are going to write some iterative and recursive versions of the same

function. Iterative versions use loops, recursive versions do not use loops,

and instead contain calls to themselves but on a smaller problem. I’ve given

you the code for an algorithm we have seen before — a for loop that sums all

integers between 1 and n:

def iterativeSum(n):

total = 0

for i in range(n):

total = total + (i+1)

return totalTogether, we’ll write a recursive function that accomplishes the same task.

Tips for Recursion

For any recursive problem, think of these questions:

-

What is the base case? In what instances is the problem small enough that we can solve the problem directly? Sometimes you may need more than one base case, but rarely do you need several.

-

What is the recursive call? Make one or calls in the function to itself. It is very important to use different arguments (usually "smaller") in the recursive call otherwise you obtain infinite recursion.

-

Do all possible chains of recursion lead to a base case?

-

If a recursive function is supposed to return a value, make sure all cases return a value and that recursive calls do something with the return value of the smaller problem before returning.

Exercise: Factorial

Recall the iterative version (using a loop) of factorial that takes a positive

int value, n, and returns the product of the first n integers. Try writing a

recursive version of the factorial function in factorial.py.

Exercise: Interpret a Recursive Function

Open countdown.py, and working with a neighbor, do the following:

-

Explain the program to your neighbor.

-

What is the recursive function doing?

-

Identify the base vs recursive case?

-

Are you sure that all recursive calls eventually hit the base case?

-

Assuming the user inputs

4, draw a stack diagram at the time the program prints "blastoff".

Exercise: Reversing a List

Next, we’ll use recursion to work with lists. In listReverse.py, write a

function that takes in a list and returns a new list that contains the input

list’s items in reverse order.

Wednesday

Here is the simple blastoff(n) function, to show a countdown from some number n, using a for loop:

def blastoff(n):

for i in range(n,0,-1):

print(i)

print("blastoff!")

Thinking recursively, you may notice that blastoff(10) is really just this:

print(10) blastoff(9)

And blastoff(9) is this:

print(9) blastoff(8)

And so on. The key to writing an algorithm recursively: handle the first item or case, then

let recursion handle the rest. For the above, given an integer n, we would:

print(n) # take care of n blastoff(n-1) # let recursion handle the rest

Also note, each subsequent call to blastoff() has a smaller value of n.

Eventually we will call blastoff(2), then blastoff(1), and then, finally, blastoff(0).

At that point, we want to just print "blastoff" and stop the recursion. This is formally

called the base case, and is usually written with an if/else clause.

Here is the full recursive blastoff function:

def recursiveblastoff(n):

if n <= 0:

print("blastoff!")

else:

print(n)

recursiveblastoff(n-1)Notice the base case stops the recursion (does not call another copy).

Also notice the non-base case (the else clause) heads toward the base case

by calling another copy, but with n-1 as the argument.

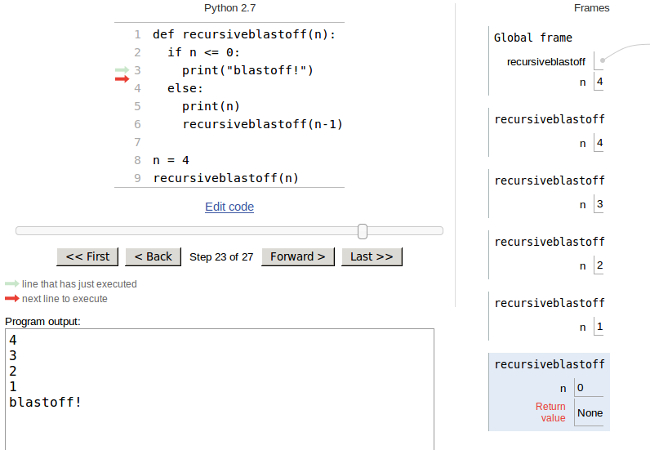

Sometimes, to understand recursion, it helps to think about the stack frames.

If the above function were called with n=4, how many frames would be put

on the stack? Try it in the [python tutor](http://www.pythontutor.com)!

Here is a screenshot of the stack frames,

when the recursion has reached the base case:

The factorial(n) function is

defined as n*n-1*n-2*…3*2*1. So, for example, factorial(5) is just

5*4*3*2*1. Notice, however, that factorial(5) *can be written as just

5*factorial(4), since factorial(4) = 4*3*2*1. If factorial(0) = 1, can

you write a recursive factorial function? You can test your function against

the factorial function in the math library:

>>> from math import factorial >>> factorial(5) 120 >>> factorial(8) 40320

Note: both the factorial() and the blastoff() functions can easily be written without using recursion. We are just using them as simple examples. This week we will try to write as many recursive functions as we can, just to learn recursion and get used to thinking recursively. Later in the week we will look at some algorithms that are more easily expressed using recursion.

thinking recursively

I think the hardest part about writing recursive functions is the first step, where you need to express the problem in a recursive fashion. Try to keep the following in mind: handle the first case, then let recursion handle the rest. Once you have that part figured out, it is usually easy to write the base case. Let’s try a few examples:

sum a list

Given a list of numbers, L, write a recursive function (no for loops!) to

sum the list and return the result.

The first step is usually the hardest…the sum of a list is just L[0] + the sum of

the rest of the list. Using python slicing, it is easy to grab the rest of the list: L[1:].

If sum(L) calls sum(L[1:]), what is the base case we are heading toward? And if we

reach the base case, what should the function return?

flipping coins

Given a positive integer n, flip a coin n times and return the number of heads flipped.

Write a recursive coinflip(n) function (again, no for loops!).

Note that n flips is just one coinflip plus n-1 more flips. So our function, in the

non-base case, needs to flip 1 coin, figure out if it was heads or tails, then let

recursion flip the other n-1 times, add those to the result of the first flip, and

return the full result.

Each subsequent call to coinflip() has one lower value of n, so what is the base

case?

counting items in a list

Given a list of numbers, L, and a value, x, write a recursive function to

count how many of x are in L. For example, calling count(range(10), 99) would

return 0, and count([1,2,8,2,2], 2) would return 3.

Again, handle the first item in the list, L[0], then let recursion handle the rest of the list (L[1:]).

is the list sorted?

Here is the isSorted(L) function from last class:

def isSorted(L):

"""return True if list is in sorted order, low to high"""

if len(L) <= 1:

return True

else:

# check L[0] vs L[1]

if L[0] > L[1]:

return False

else:

return isSorted(L[1:])For the base case, we know the answer: a zero- or one-element list is

obviously sorted, so return True.

For the non-base case, just check if the first two are in order. If not,

we can immediately say the list is not in order (return False). If the

first two items are in order, make the leap of faith: isSorted(L[1:])

will give us a True or a False, if the rest of the list is sorted

or not, so just return whatever we get back from that recursive call.

Friday

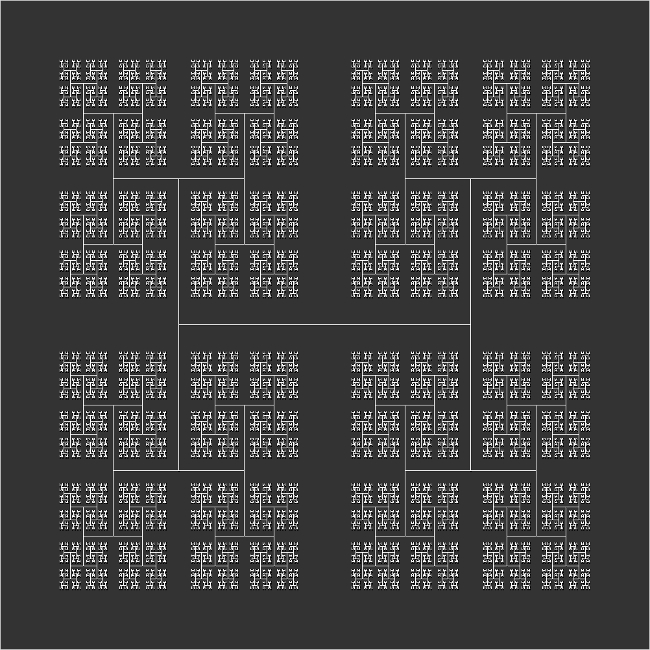

recursive graphics

Finally, now that we understand recursion a little better, here are some examples that are "naturally recursive". These are algorithms that are easier/more elegant to write using recursion. Again, you could write them iteratively (using loops), but sometimes it makes more sense to use recursion (not always!).

Here is an interesting picture. Can you see the recursion? What happens first, and what is the base case?

Using

Zelle Graphics

first write a function called H(win, pt, size) that draws

a single "H" in the given graphics window, at the given Point pt, with the

given size. For example, calling H(win,Point(100,100),50) would draw an

"H" at the coordinates (100,100) with size 50.

For the "H" function, you will need to create Line() objects using other

Point() objects. Using the clone() method will definitely help:

>>> from graphics import * >>> pt = Point(100,100) # assume we are given these >>> size = 50 # assume we are given these >>> >>> p1 = pt.clone() >>> p1.move(-size,-size) >>> p2 = pt.clone() >>> p2.move(-size,size) >>> leftedge = Line(p1,p2) # create left edge of the H >>> leftedge.draw(win)

Once you have a working H() function, can you use it to draw one "H",

then another at point p1? And another at that H’s p1? And so on…

What is the base case for the recursion? What happens when the size gets

too small? Also, how many times do we need to recur to get the four H’s

at the four corners (points p1, p2, and so on)?

more graphics examples

There are many interesting examples of recursive graphics algorithms. Take a look at some of these links and see if you can understand how they recur:

merge sort

Here is the mergeSort() algorithm from last week:

def mergeSort(L):

"""use merge sort to sort L from low to high"""

if len(L) > 1:

# split into two lists

half = len(L)/2

L1 = L[0:half]

L2 = L[half:]

# sort each list

mergeSort(L1)

mergeSort(L2)

# merge them back into one sorted list

merge(L1,L2,L)For this one, the base case is not explicitly written. It just does "nothing" if the length of the list is one or less.

Any divide-and-conquer algorithms, like the merge sort, can usually be expressed easily using recursion.

analysis of merge sort

Since merge sort simply divides the original list in half, then each subsequent

list in half, and so on, part of the big-O notation must be logN, because that’s

how many times we can divide a list of size N in half. The other part of merge

sort is to merge them all back together. Given two sorted lists, the merge operation

just compares the first items in each list. This will require at most N compares,

so it’s not hard to see that the merge sort is an O(NlogN) algorithm. This is

better than all of the quadratic sorts we looked at last week (bubble, selection,

and insertion sort).

Here is a nice picture from wikipedia of what happens during the merge sort.

And here are some timings (for initially random lists of N integers) of various sorts we have looked at:

$ python timesorts.py

N: 2000

selection sort time: 0.1435

bubble sort time: 0.4378

python sort time: 0.0003

merge sort time: 0.0090

$ python timesorts.py

N: 4000

selection sort time: 0.5572

bubble sort time: 1.7164

python sort time: 0.0007

merge sort time: 0.0188

Notice the time for the merge sort does not quadruple like the selection and bubble sort times. Also, python’s built-in sort seems to be the best. What algorithm does the built-in sort use???